MODERN AUTO LEGEND, FERRARI CEO SERGIO MARCHIONNE, HAS DIED AT 66

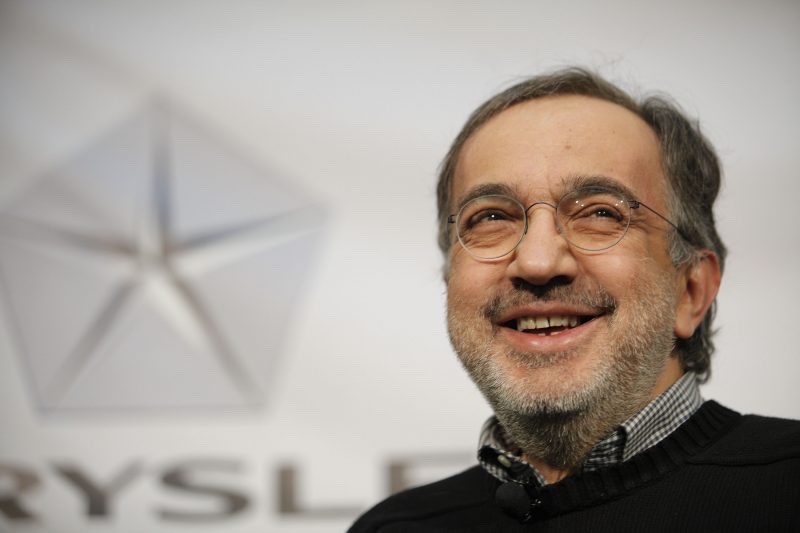

FCA CEO Sergio Marchionne addresses the media during a celebration of the production launch of the all-new 2017 Chrysler Pacifica minivan at the FCA Windsor Assembly plant in Windsor, Ontario, May 6, 2016. REUTERS/Rebecca Cook

Former FCA and Ferrari CEO Sergio Marchionne. Thomson Reuters

Former FCA and Ferrari CEO Sergio Marchionne. Thomson Reuters

- Former FCA and Ferrari CEO Sergio Marchionne has died at age 66.

- He had reportedly been in a coma in intensive care at a hospital in Zurich after complications from surgery.

- The boards of FCA and Ferrari named his replacements following emergency meetings over the weekend.

- Marchionne was an auto industry legend, leading a turnaround at Fiat and taking Chrysler from bankruptcy to renewed prosperity.

Sergio Marchionne, the outspoken former CEO of both Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA) and Ferrari, has died at age 66.

FCA Chairman John Elkann said in a statement, as cited by Reuters: “Unfortunately, what we feared has come to pass. Sergio Marchionne, man and friend, is gone.”

Marchionne was recovering from shoulder surgery when his condition took a turn for the worse. It was unclear from various news reports whether Marchionne’s illness has been more serious. He fell into a coma at a hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, and was placed on a respirator in intensive care.

This past weekend, the boards of both FCA and Ferrari met during emergency sessions to choose replacements for Marchionne when it became apparent that his condition was grave.

Marchionne was the unlikeliest legend in the modern auto industry. An accountant by training, he was born in Abruzzo region of Italy in 1952 but moved to Canada as a teenager. He was educated at Canadian universities and started his career at Canadian firms before returning to Europe. Prior to joining Fiat’s board of directors in 2003, he had no experience in the auto industry. He was named Fiat’s CEO in 2004.

“Four years ago, Fiat was a laughingstock,” Marchionne wrote in the Harvard Business Review in 2008.

“Whenever you opened a newspaper in Italy, there was another embarrassing story: Fiat had lost more money; its new car had flopped; a strike was on somewhere. Even more worrying to me was the fact that the company had gone through four CEOs in three years. Imagine showing up in June 2004 and being the fifth guy to try to resuscitate what appeared to most people to be a cadaver.”

Marchionne went on the remake Fiat and its culture, trademarking his tireless, dynamic, demanding style along the way.

Bringing Chrysler back from the brink

The stage was set for an unexpected takeover of Chrysler, which had to be bailed out during the financial crisis in 2009. Bankruptcy followed, and the Obama administration’s Auto Task Force was ready to let the smallest of the Detroit Big Three go. Dealing with the multi-billion-dollar bailout and bankruptcy of General Motors at the same time was the higher-priority problem.

Chrysler had languished for years, first after being acquired by Daimler and later under management by Cerberus Capital Management, a private equity firm. Fiat and Marchionne were the last hope for the carmaker, founded in 1925 by Walter Chrysler (the company had already been saved once before from extinction by the government, in the late 1970s).

With billions in restructuring financing arranged by the Obama administration and the Auto Task Force eliminating much of Chrysler’s debt, Marchionne was able to steer the carmaker back to prosperity as the US recovered from the Great Recession and the US auto market set new annual sales records.

Fiat bought the government’s and the United Auto Workers’ stakes in the new Chrysler, and Marchionne staged a successful IPO in 2014, just as the company’s RAM and Jeep brands were benefiting from a resurgence of pickup trucks and SUVs.

Taking Ferrari to the next level

Marchionne followed that up with a spinoff of Ferrari from the newly formed FCA in a 2015 IPO. Marchionne had struggled with longtime Ferrari head Luca di Montezemelo over expanding production of the storied Italian supercar brand, which Montezemelo wanted to keep at 7,000 vehicles a year. Marchionne had 10,000 in his sights.

He took on the dual role of CEO and chairman, and he also oversaw Ferrari’s Formula One racing campaigns. (Marchionne was a Ferrari enthusiast and avid, if not always accident-free, driver: he crashed a 599 GTB in 2007, and he also owned a black Ferrari Enzo, named for the founder of the prancing-horse marque.)

On Wall Street, it was speculated that he might consider similar spinoff IPOs of Maserati, Alfa Romeo, or both. But he had also announced his intention to retire as FCA CEO in 2019, leaving the technicalities of such decisions to his successor, who hadn’t yet been named at the time of his illness (he planned to stay on as CEO of Ferrari until 2021).

Marchionne was unflinching in his negative views of how the global auto industry was managed — often incompetently, he thought — and how it obliterated cash. In 2015, he produced a scathing analysis of the business’ inefficiencies, titled with typical flair “Confessions of a Capital Junkie” and subtitled “An insider perspective on the cure for the industry’s value-destroying addiction to capital.”

The presentation was widely circulated and discussed, as it bolstered Marchionne’s case that the auto industry was rife with redundant technology development, addicted to easy money, and determined to maintain far too much manufacturing capacity.

Pushing FCA into an uncertain future

But as effective as Marchionne was in merging Fiat and Chrysler, his efforts to court the largest US car maker failed in 2015. After a noisy campaign to conjoin FCA and GM, Mary Barra exercised her power as GM CEO to rebuff Marchionne’s advances and leave him to the task of preparing FCA for his departure.

This he did in consistently entertaining fashion, working the global auto circuit with his appealing combination of straight talk and edgy jokes. He rarely shied away from a bold position, arguing for example that electric cars were a costly waste of time no matter what Tesla and CEO Elon Musk thought (he changed his mind on that score in 2017 and 2018 and was taking electrification more seriously).

He also sought out a partnership with Alphabet’s Waymo unit on self-driving cars to help FCA catch up on a technology that it lacked the resources to invest in as it paid down debt on its balance sheet. And he was readying Ferrari to launch its first-ever SUV, as well as a possible electric supercar.

And he recognized earlier than the rest of Detroit that a decisive consumer shift away from passenger cars to SUVs, crossovers, and pickups was underway; he committed FCA to a nearly all-truck portfolio in the US years ahead of the competition.

Work, work, more work — and sweaters

Marchionne was a noted workaholic. “Being a leader at Fiat is a lifestyle decision,” he wrote in the Harvard Business Review. “It’s not the Buena Vista Social Club.” With Fiat and Ferrari in Italy, FCA headquartered in London, and Chrysler’s operations based in Auburn Hill, Michigan, he traveled often and everywhere, usually in his uniform of a black sweater and pants, an antidote to the industry’s armor of tailored suits (he claimed he bought his signature threads in bulk, online, in the middle of the night — and always on sale). He didn’t seem to sleep much, and until recently, he was fueled by cigarettes and espresso.

He enjoyed jousting with analysts on earnings calls and would mix it up with reporters at car shows like a sort of cheerfully disheveled, bespectacled, prosperous philosophy king with jaded macro-economic view of the world, but he rarely granted one-on-one interviews. To the end, he referred to FCA and Ferrari, in the charmingly antiquated language of aristocratic commerce, as “houses.” He had an MBA, but he never talked like a bureaucrat.

He’s now left both houses in monumentally better shape than they were before he arrived on the scene. When Marchionne’s condition declined, John Elkann — scion of the Fiat-founding Agnelli family and FCA’s chairman — wrote in a statement to FCA employees that it was “a situation that was unthinkable until a few hours ago, and one that leaves us all with a real sense of injustice.”

For the rest of the industry, Marchionne’s death leaves us without a true original and a leader who always sought to balance opportunistic optimism and flinty realism, hard work and humor, the world of business and the realms of life.